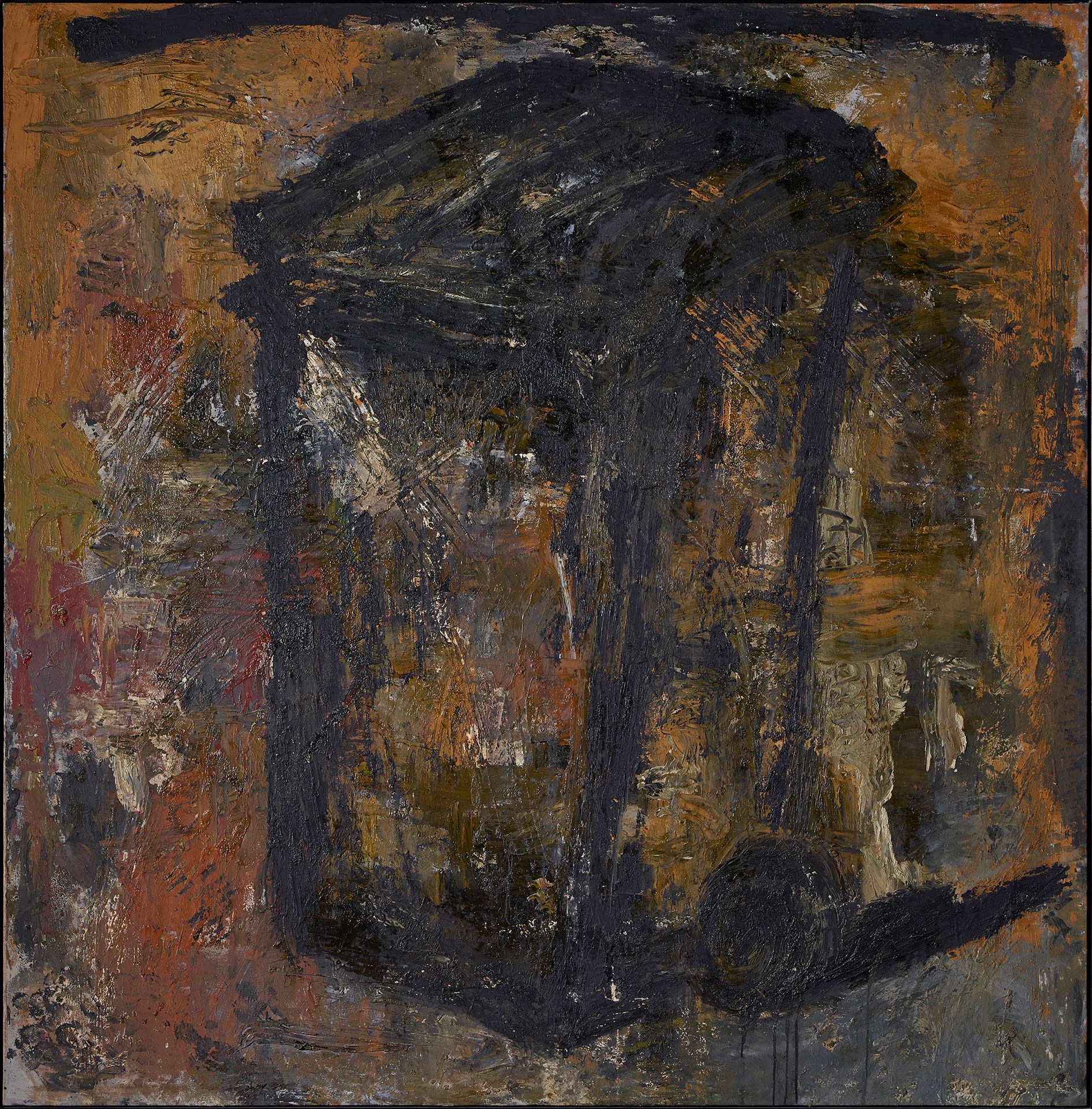

José María Sicilia (Madrid, 1954)

Rubbish Bin

1984

WORK INFORMATION

Mixed media on canvas, 247 × 242 cm

OTHER INFORMATION

Inscription on the reverse: "Cubo de basura / Sicilia"

José María Sicilia is one of several artists who energetically burst on the art scene in the early 1980s. After studying at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Madrid, he moved to Paris in 1980 and had his first shows there. After Sicilia's first exhibition in Madrid, held at Galería Fernando Vijande in 1984, he quickly came to be regarded as one of the greatest talents of his generation, along with Barceló, Campano, Broto and others. That solo show featured large-format paintings with impressive impasto in a style close to the then dominant trend of Neo-Expressionism, although Sicilia never considered himself a member of any particular movement. On dense, colourfully impetuous grounds, Sicilia painted a series of objects outlined in thick dark strokes, each of which was the sole protagonist of a picture. These were ordinary objects found in the studio: scissors, vacuum cleaners and kitchen utensils that transform the magma-like backgrounds of colour, introducing motifs slightly reminiscent of Pop Art. Cubo de basura [Rubbish Bin] pertains to that group of works. This combination of seemingly antithetical languages—"cold" pictorial techniques and spot inks on the Pop side, versus the strongly suggestive pictorial matter—is part of the often eclectic creative options that characterised painting in the 1980s. In an interview for the journal Figura given that same year, Sicilia qualified his intentions: "I do not paint the object, but rather the feeling it gives me. None of my pictures contain a theory, every painting is a fumbling step in the dark."

Flor azul [Blue Flower] corresponds to a different pictorial phase in New York, where Sicilia lived for a time in 1985 and exhibited at the Blum Helman Gallery. It was a period of growing international fame, when his painting was evolving towards abstraction. The flower became one of his motifs, an image frequently found in Western and Eastern poetry and painting in conjunction with other flowers or with gardens, fields and bouquets, although it is also present in many ancient and modern rituals. This bloom, unlike other flowers Sicilia painted around the same time, is not depicted or defined as such, and its forms disintegrate in the density of the surface, the painting's epidermis. The flower is transfigured until all that remains is a name, a poetic allusion. Years later, in the 1990s, the flower would resurface, recovering its form, petals and colouring, and be translated into another material, wax. Here the elements are reduced and the picture is structured in planes with a very polished surface, lacking the pastose brushwork of his early pieces. The painting is divided into two parts: the upper register offers a stunning visual spectacle with its intense, glowing blue; and the lower section, with an equally textural surface, features vague forms in ochres, greens and reds that might suggest an organic background, the matter—the paint—in which everything germinates.

In Untitled we must have sharp eyesight to make out the different tones of white. The use of only one colour does not signify visual monotony; on the contrary, it requires a greater effort to discover its wealth of subtle nuances. This painting continues the long tradition of monochrome painting in the 20th century—Malevich, Ad Reinhardt, Yves Klein, Piero Manzoni, Robert Ryman, etc.—and even its square format is a nod to Malevich's Suprematism. Sicilia began producing these types of works in the late 1980s and carried on through the 1990s, replacing oils with waxes and paraffins. Here he was still extracting qualities of translucent matter from oil paints. His interest in light is expressed using dense, opaque colours. Objects and animal figures reappear, diluted on the white surface yet still perceptible thanks to the varying transparencies of the layers of oils. These figures, generally situated in the centre of the picture, are rendered with a vagueness that makes them seem more like vestiges or traces than corporeal forms. From his earliest works, Sicilia's attention had always been centred on the presence of objects, but in these white paintings that relationship culminates in fusion, in enigmatic incorporation. Years later, Sicilia wrote, "When I turned round, I saw shadows [...] these shadows had come to quietly infiltrate my dreams without me noticing; they did not move, they made no noise, they emitted no reflection: they were grey, pale, bluish." [Carmen Bernárdez]